‘It’s truly unacceptable that half of the world’s 160 million child labourers are very young’

According to studies by UNICEF and the International Labour Organisation (ILO), 160 million children worldwide are in child labour. For the first time in 20 years, child labour has increased. Suzanne Laszlo, director of UNICEF Nederland, and Pauline Neefjes, senior advisor to UNICEF’s Better Business for Children programme, give the facts behind the figures.

The last study, which dates from 2016, showed that there were 152 child labourers worldwide. What was the situation in 2020?

Suzanne: ‘It’s sad to have to conclude that the number of child labourers has increased by 8.4 million. In 2020 160 million children under 18 were doing some kind of work. But it’s even sadder to see that the number of very young child labourers – between the ages of 5 and 11 – has risen enormously, and that they now make up half of the total. We’re talking here about 80 million young children. That’s truly unacceptable and calls for more effort on the part of all those involved.’

What else do the figures show?

Pauline: ‘Half of the children in the 5 to 17 age group do hazardous work. Seventy-nine million children are doing work that can seriously harm their health, safety or morals. That’s 6.5 million children more than in 2016. It’s heartrending to conclude that children in the youngest age group – between 5 and 11 – are just as likely to be doing hazardous work as older children. These children will be marked for life. They should be spending their days at school and enjoying their free time, but now they see their see their future prospects crushed in endless, monotonous work.’

Is the coronavirus pandemic the reason for this increase?

Pauline: ‘Child labour has increased in Sub-Saharan Africa in particular. That region now accounts for 50% of the world’s child labourers. That’s not just because of population growth and recurrent crises, but also – and chiefly – because of extreme poverty through slow economic and technological development. Extreme poverty forces parents to send their children to work. And unfavourable trade relations don’t exactly help. Many countries in Sub-Saharan Africa have a persistently low GDP, so that governments have too little money to spend on social provision like financial support, child benefit and high-quality education. To make matters worse, figures from the rest of the world show that the downward trend has now stalled. And the impact of the coronavirus pandemic has yet to be taken into account.’

Suzanne: ‘The report warns that as a result of the pandemic, another nine million children run the risk of being forced into child labour by the end of 2022. A simulation model shows that this number could rise to 46 million if the world continues to turn a blind eye. As members of the United Nations, we pledged in 2000 to have eliminated child labour by 2025. This calls for solidarity. Governments, businesses and consumers need to work together to turn the tide. UNICEF is therefore calling on them to make a serious investment in the countries where child labour is so widespread, to give families access to the social protection they need.’

Is the situation different in urban and rural areas?

Pauline: ‘Child labour is three times more common in rural areas than in cities. That’s because 7 out of 10 child labourers work in mining or farming – for example in cocoa and tea plantations and rice and cotton fields, or on their families’ own land, where crops are grown for local consumption. These plantations and this farmland are located outside the major cities. Two in ten child labourers work in services, selling fruit or water, shining shoes or collecting waste, for example. One in ten works in industry, in textile factories or in smelters.’

Are more boys than girls engaged in child labour?

Pauline: ‘More boys are engaged in child labour than girls. That’s because household chores often aren’t included in the figures. But if you include this work – which takes up more than 21 hours a week for girls in the 5 to 14 age group – the difference between boys and girls is much smaller.’

Do these working children attend school?

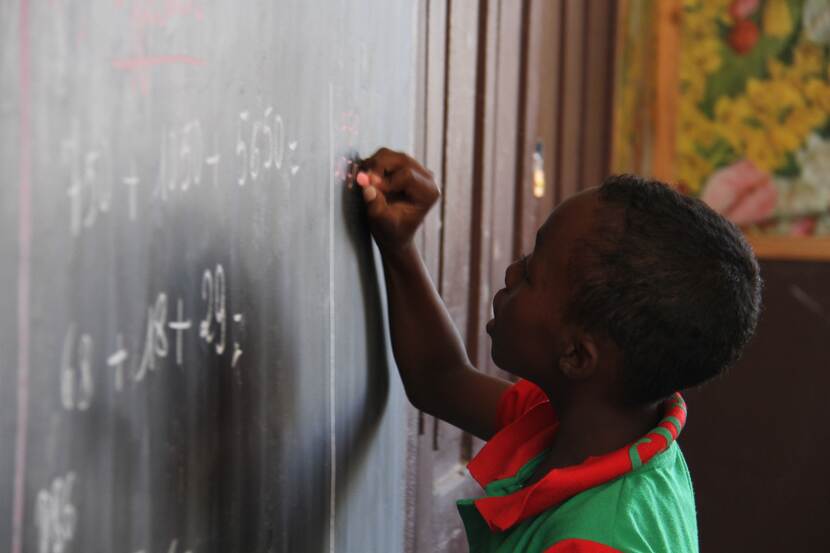

Suzanne: ‘Nearly 28% of the children in the 5 to 11 age group and 35% of the children in the 12 to 14 age group do not attend school at all. That’s a terrible thing, because education presents one of the best routes to eliminating child labour. Only high-quality, publicly funded education can break through the vicious circle of poverty and child labour, because this gives children the opportunity to develop. What’s more, children will only be able to develop both socially and mentally if, apart from school and household tasks, they have some free time to do what they want.’

What is UNICEF doing to eliminate child labour?

Suzanne: ‘It takes more than just banning children from factories, cotton fields or gold mines to eliminate child labour. Our approach is to support poor families financially, provide basic education, and talk to employers about alternatives to child labour. The Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs has launched several major programmes, with UNICEF sharing responsibility for implementation. The Ministry supports the Work: No Child’s Business alliance, enabling us to work with Stop Child Labour – coordinated by Hivos – and Save the Children Nederland to prevent child labour in Côte d’Ivoire, India, Jordan, Mali, Uganda and Vietnam.’

Pauline: ‘UNICEF also supports businesses in ensuring corporate social responsibility in the textile industry and in the metals, minerals and goldmining sectors. We help them tackle child labour in their own production chains, and in those of their suppliers.’

The Netherlands wants to eliminate child labour by 2025. What parties are needed to achieve this Sustainable Development Goal?

Suzanne: ‘Child labour is a human rights violation. It denies children the right to an education, exposes them to exploitation, and causes poverty to persist. Governments, businesses and local communities worldwide share the responsibility for preventing child labour. Child labour is a worldwide problem, calling for a global solution through cooperation between countries. To eliminate all forms of child labour, we need to gear up at every level.’

Pauline: ‘That means working with governments and international organisations to enact legislation to end child labour and organise funding for social provision like child benefit and education. Businesses play a role in preventing child labour in their production chains – through the Fund against Child Labour, for example. Civil society organisations can also launch activities to stop child labour and develop social provision.’

What do we need to do to prevent the worst case scenario happening, and another 46 million children becoming the victims?

Suzanne: ‘2021 is the International Year for the Elimination of Child Labour. UNICEF and the ILO are encouraging member states, businesses, trade unions, civil society, and regional and international organisations to make twice the effort to eliminate child labour worldwide. Let’s work shoulder to shoulder and provide adequate social protection for everyone, including child benefit. We also need to spend more on education, and work on incentives to enable all children to go to school. It’s also essential for adults to earn a decent living, so that children don’t have to help them generate a family income. And we need to end harmful gender norms and discrimination, which prevent some children from attending school. Finally, we need to invest in child protection systems, agricultural development, rural public services and infrastructure.’

And what has the reverse effect?

Pauline: ‘If a business is alerted to signs of child labour, they shouldn’t end the trade relationship immediately. It’s far better to enter into dialogue with trading partners and to seek ways of ending child labour.’

The results of the flash survey show that two out of three consumers are concerned about the products they buy having been produced by children. What can they do?

Suzanne: ‘It would be great if more people asked whether a product they plan to buy has been produced responsibly. Consumer pressure can work wonders on businesses. We’ve still got a long way to go before supply chains are transparent and responsible. But we’ve made a start. I profoundly hope that every individual – consumer, civil servant, buyer, entrepreneur or employee – will work to stop child labour. None of us would want to see our own children in child labour. So why should we accept someone else’s child having to work?’