Winner of the Human Rights Tulip: how Ayin Network is building a memory for Sudan

Weblogs

In Arabic, Ayin refers to the eye. In Sudanese dialect it means ‘to look’. It is a symbolic name for the media platform that receives this year’s Dutch Human Rights Tulip: Ayin Network. Journalists that continue to show what would otherwise remain unseen, even in the middle of a war.

|

Note |

‘We want to preserve Sudan’s memory,’ says Zain, Director of Ayin Network. ‘We document everything that happens. For now, but especially for the future.’

Ayin was founded in 2013 in the Nuba Mountains, in a region where Omar al-Bashir’s government barely allowed journalists in. Working from inside Sudan was already dangerous in those years. Ayin therefore operated in exile, with its staff scattered across the region.

A new beginning

After the fall of the regime in 2019, the organisation was able - for the first time in many years - to work openly from an office in Khartoum. The team built an archive and a small editorial hub and could collect stories without going underground.

That period did not last long. When war erupted in 2023, the office was attacked. Equipment, hard drives and thousands of hours of footage were lost. The war forced Ayin to flee once again. The team ended up back in exile, where they had to start again, almost from scratch, for the second time in ten years.

Citizen journalists

When the war broke out, Sudan’s media landscape collapsed almost overnight. Many journalists fled, newsrooms shut down, and large parts of the country were cut off from the internet. Ayin Network had to reinvent itself. ‘We now work mainly with citizen journalists,’ says Nabra, from the Ayin team. ‘People without a professional background, but who are in the right place to show what is happening.’

Sometimes it takes weeks to find someone who can safely gather information in a particular area. But that same person may have to flee again a few days later. Despite these challenges, Ayin now has contributors in twelve of Sudan’s eighteen states, as well as in several refugee settlements outside the country.

No breaking news

Although Ayin has a wide network of reporters, they rarely publish breaking news. There is a reason for that: ‘There is too much misinformation,’ Zain explains. ‘We take our time.’

Every Tuesday, the team publishes one detailed, fully verified news briefing, pieced together from dozens of reports across the country. It is slow news, deliberately so. In Sudan, speed quickly turns into rumour.

Alongside this weekly briefing, Ayin Network produces longer investigative pieces: on the gold trade, on illegal mining, and on the exploitation of gum arabic. Not to mention the use of child soldiers and human trafficking.

Phone in a sock

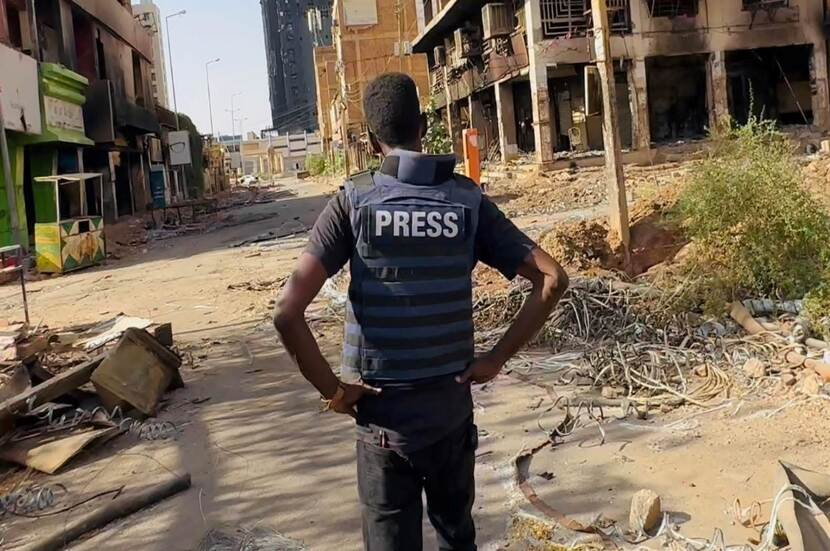

Reporting in Sudan has never been safe, but this war has brought the danger to an entirely new level. Journalists cannot work openly. A press badge in Sudan is more of a target than a protection. Zain recounts how colleagues sometimes hide their phone in a sock when passing through checkpoints.

‘On the first day of the war, a kill list appeared online,’ Nabra says. ‘Journalists were publicly labelled as enemies. You see your own colleagues on social media, with calls to kill them. It shakes you to your core.’

One of Ayin’s reporters in Al-Fasher went missing for ten days. The team did not know whether he had escaped the city, been detained, or worse. When he finally made contact, he was hiding somewhere, exhausted but alive.

The psychological strain is just as severe. Zain describes how reporters sometimes call in tears because they can no longer cope with the violence they are documenting. Even inside the newsroom the constant flow of brutal images and stories takes its toll.

Why stopping is not an option

Why continue, despite all the risks? ‘Because people need us,’ says Zain. We reach four million people every month. More than half of them are still inside Sudan. They use our information to decide whether they should flee, stay, or wait. That is an enormous responsibility,’ Zain says. ‘We cannot abandon them.’

What the world still doesn’t see

Much of what happens in Sudan remains invisible to the outside world. Zain stresses that many observers misunderstand the scale of the crisis, especially the rapid rise of militias. Since the start of the war, dozens of new armed groups have emerged, some supported by warring parties, others formed by communities trying to protect themselves. ‘There are now more than eighty,’ he says.

Nabra points to another issue: the way international media simplify the conflict. The information exists, she says, but the story is complex, with no clear good or bad side. As a result, Sudan is often ignored or reduced to numbers: hunger, deaths, displacement.

What is needed

Much is required to keep Ayin’s work going. With hundreds of professional journalists having left Sudan, there is a huge gap. New reporters need training: how to work safely, how to protect sources, how to verify information. Many of these conversations happen over unstable connections and under intense time pressure.

Equipment and storage are other constant concerns. Cameras disappear during raids, phones are confiscated or damaged as people flee. It shows how vulnerable the work is.

The biggest challenge, however, remains safety. Reporters are at daily risk, and arranging safe routes, shelter or emergency support takes time and resources.

Human Rights Tulip

Under these circumstances, winning the Dutch Human Rights Tulip means a great deal. It is recognition of their work. ‘It shows that people outside Sudan understand the pressure we are working under,’ Zain says.

Nabra hopes the award is also seen as a tribute to all Sudanese journalists who can no longer do their jobs. Nabra: ‘Since 2023, at least fourteen journalists have been killed in Sudan, according to the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ), which only counts journalists killed in the line of duty. However, the Sudanese Journalist Syndicate reports that 32 journalists have died, some while on duty and others not.’

Yet there is always something that brings hope, says Zain. ‘When we see that a story we publish helps someone. When followers start raising money for a family in need. And every time someone says at the end of an interview, ‘We only want peace,’ that is what we try to pass on to the world.’